When I speak with people about the idea of “wisdom in our own backyards,” I often think of a proud elderly man I met twenty years ago on a rural island off the coast of South Carolina, who was fiercely determined to retain ownership of the land that had been purchased by one of his ancestors, a freed slave. A towering yet dignified gentleman in his eighties, George Washington embodied a feeling that I believe we all share — the hope that the next generation will not forget the ideas and beliefs that have been so important to us during our lifetime, and the desire to see our message passed along to the next generation.

I met Mr. Washington on St. Helena Island, one of South Carolina’s Sea Islands not far from the historic town of Beaufort, which moviegoers have seen in “The Big Chill” and “The Prince of Tides.” One of St. Helena Island’s neighbors is the popular golf mecca and tourist destination of Hilton Head Island.

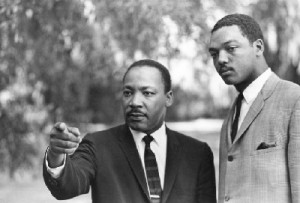

As Union troops seized victory during the Civil War, hundreds of slaves who had been brought to St. Helena Island to till the marshy land of numerous rice plantations there, the federal government established the first school for freed slaves there, naming it “Penn Center.” A century later, during the 1960s, Rev. Martin Luther King and other civil rights leaders spent time at the school to make their plans for the freedom movement of their time, inspired by the freedom claimed by those on that very same island many years earlier.

Thanks to its remote location and distance from the larger cities of Charleston and Savannah, St. Helena Island was able to preserve what is known as the “Gullah” culture, a mixture of influences from Africa and other lands.

Along with their freedom and access to education, thanks to Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, every freed slave was also given property and the opportunity to cultivate that land — a reparation policy following the abolition of slavery that became known as “forty acres and a mule.” (Film director Spike Lee made use of this expression when he was choosing a name for his production company.) Following the Civil War, the island also became known for the beautiful baskets made by a number of residents from the tall seagrass in the area. A number of years later, this gift was rescinded but freed slaves were given the opportunity to work and save money as sharecroppers, and then purchase the land for $1.25 per acre. (During this era, mot prosperous white landowners saw this marshy land as undesirable.)

Over the years, I’ve forgotten whether Mr. Washington was the great-grandson or great-great-grandson of the freed slave who purchased a large tract of land on the island that featured a spectacular 180-degree view of the bay. I do, however, recall that Mr. Washington was troubled by the fact that his adult children and grandchildren had left their South Carolina roots behind and moved to more stimulating urban cities like New York and Philadelphia. Not long before CBS News correspondent Betsy Aaron and our camera crew visited Mr. Washington as we filed a story about Penn Center, he told us that a real estate developer had offered him a “blank check” for his land, recognizing its “potential” as a site for condominiums or an upscale gated community. In my conversations with Mr. Washington, I once again found proof that Charles Kuralt was right when he said that it’s not necessary to hold impressive credentials or a fancy title to have wisdom and a message worth hearing.

As a I recall, Mr. Washington passed away shortly before my story about Penn Center aired in the early 1990s, but I will never forget the time I spent with him in this unique location. What did I learn from this descendant of freed slaves and the passion he felt for the beautiful land he called home? I was reminded that each of us also feels passionately about a cause, or idea, or tradition — and we all feel the urge to share this passion with others. If this desire resonates with you, too, I encourage you to take action now to share your message with others — by putting your thoughts into writing, or perhaps through a video message. Long before the age of social media, author and historian Studs Terkel recognized the power of “oral histories” and won numerous awards for documenting the stories of “average people” — and readers loved his books because, of courage there are no “average” stories. Each one is inspiring, important and well worth listening to or reading. Charles Kuralt believed in the power of stories like these too of course. I can assure you that it can be remarkably fulfilling to share your message and know that you are truly heard and appreciated.